The Eurozone: The Next Liquidity Injection for Bitcoin

Inside the ECB's Dilemma: Supporting the Eurozone Amid Rising Debt-to-GDP Ratios, and Bitcoin’s Appeal as a Debt-Free Alternative

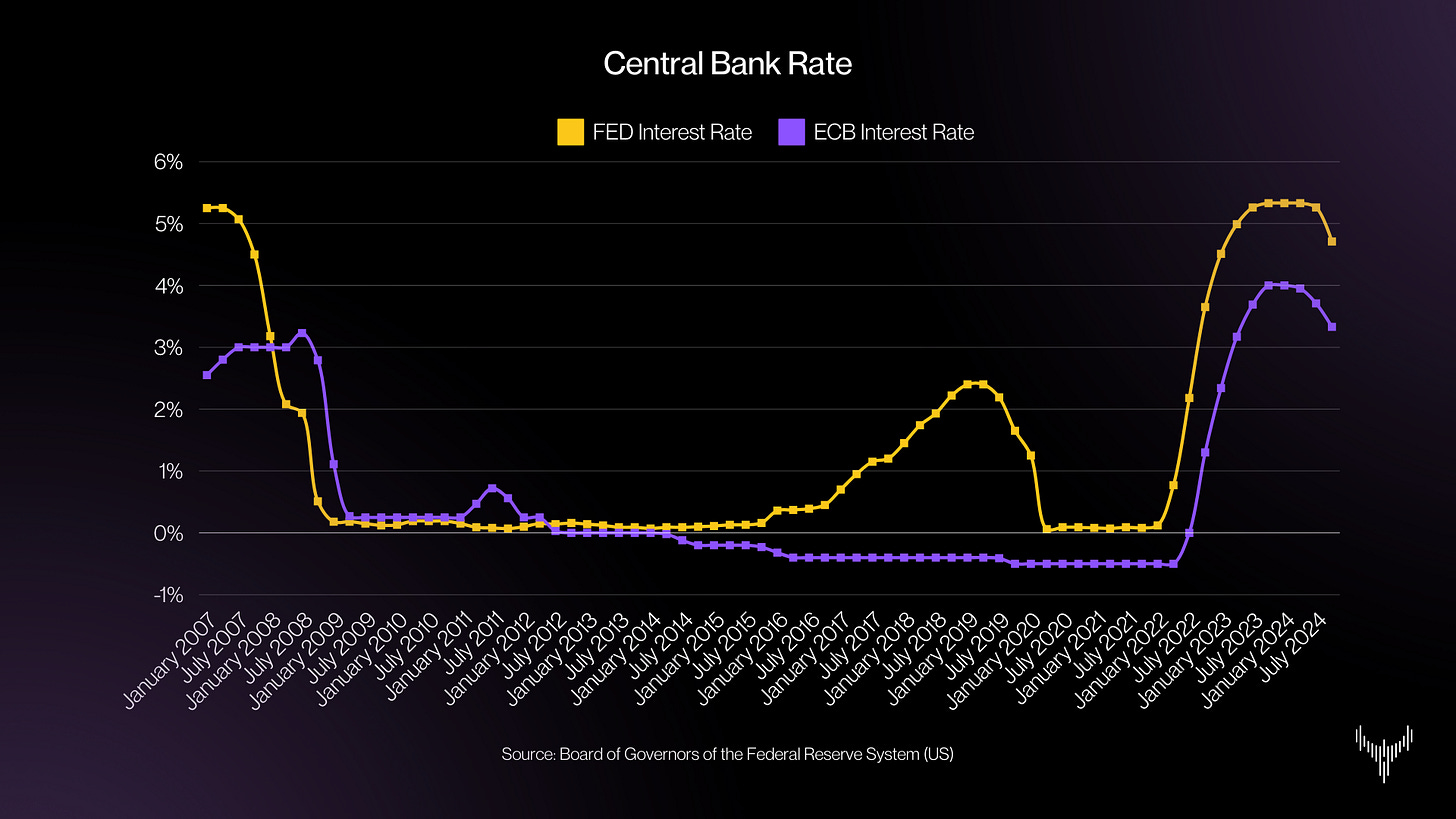

In recent years, central banks like the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Federal Reserve System (FED) have significantly reduced their balance sheets through quantitative tightening while implementing restrictive interest rate policies to combat rising inflation. Risk assets such as stocks and digital assets have shown strong performance despite these measures. This is particularly noteworthy, given that interest rates in the U.S. and Europe have returned to levels last seen in 2008, with rate hikes stopping around the end of 2023.

Bitcoin, in particular, has performed well during this period, reinforcing its role as a hedge against government debt, fiat currency risks, and Modern Monetary Theory's potential misuse. Its appeal as an alternative to traditional financial systems grows amid mounting government debt and fiscal irresponsibility. As governments overspend and central banks step in to support economies, the resulting interventions could heavily impact financial markets and the broader economy.

While the Fed often dominates financial discussions, the ECB's equally sizable balance sheet underscores its global market impact. The Eurozone's 20 member states face unique challenges, including diverse regional debt-to-GDP ratios. Despite recent quantitative tightening, the ECB's dollar reduction surpasses the Fed's. This article focuses on pressing developments in Europe, with a separate report analyzing U.S. policies under the Trump presidency and their implications for the Fed.

Project Eurozone

The Eurozone is a unique initiative uniting multiple European countries under the euro. Since its inception, it has grappled with economic disparities among member states.

The global financial crisis highlighted these challenges, particularly in Greece, Ireland, Spain, Italy, and Portugal, where debt crises exposed existing vulnerabilities. The Troika—comprising the European Commission, ECB, and IMF—played a central role by providing bailouts and implementing reforms. The ECB maintained low interest rates for nearly a decade, stabilizing the Eurozone, fostering recovery, and enabling affordable financing for debt-laden countries.

From 2009 to 2022, near-zero interest rates supported debt financing and economic growth. However, rising inflation—fueled by global supply chain disruptions, stimulus measures, and the Russia-Ukraine conflict—forced a policy shift. Higher energy prices further strained economies.

The key question is how monetary policy will adapt. With many Eurozone countries still burdened by high debt, the ECB may need to revisit low interest rate policies or purchase government bonds to manage yields and ensure economic stability.

Germany, France, and Italy, the Eurozone's largest economies, contribute over 50% of its GDP, underscoring their pivotal role. The ECB’s future monetary policy will closely track their performance due to their significant influence.

We begin with France's political situation, where recent events have widened the spread between its 10-year bond yields and Germany's.

Political Turmoil in France

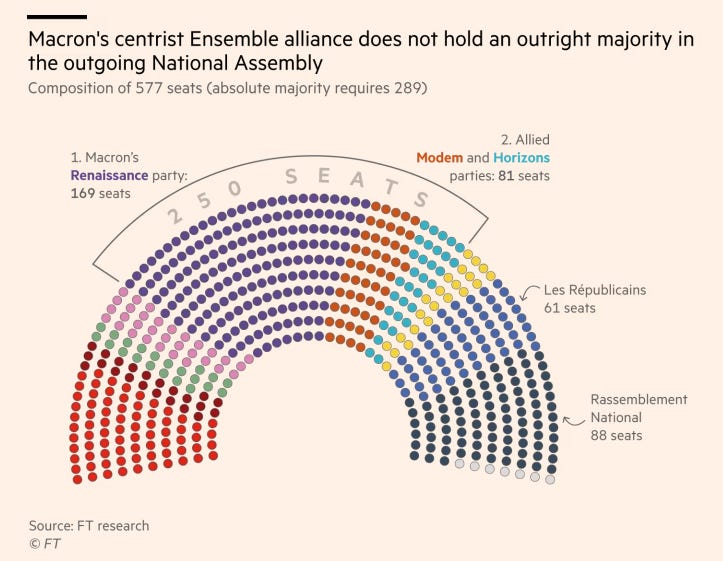

France's current political instability began with Emmanuel Macron’s decision to call snap elections following his centrist alliance's poor performance in the European parliamentary elections. Marine Le Pen’s far-right Rassemblement National (RN) claimed 31.4% of the vote, dwarfing Macron’s alliance at 14.6%. Seeking to restore legitimacy and political direction, Macron dissolved parliament, but the snap elections only deepened divisions. The resulting hung parliament is now split into three major blocs: Macron’s centrist Renaissance party, the far-right RN, and the left-wing coalition led by France Insoumise.

France’s fragmented parliament quickly created governance challenges. Michel Barnier, appointed prime minister to lead a minority government, struggled to secure parliamentary support. His administration collapsed in December after just three months, following a no-confidence vote over a deficit-cutting budget, highlighting the government’s inability to navigate the fractured political landscape.

François Bayrou succeeded Barnier as prime minister, bringing political experience but inheriting the same obstacles: a divided parliament, economic strain, and the urgent need to pass a stop-gap budget to prevent a government shutdown. The deep divisions within the assembly and the rise of far-right and far-left forces have made coalition-building nearly impossible, leaving the government vulnerable to repeated disruptions.

France’s fiscal outlook is increasingly dire, with a deficit of 5.5% in 2023, projected to rise to 6.3% by 2025, and a debt-to-GDP ratio expected to climb from 113.3% in 2024 to 120% by 2027. On December 14, 2024, Moody’s downgraded France’s credit rating, citing political instability and limited prospects for deficit reduction.

To understand these challenges more fully, it is essential to analyze France’s economic and fiscal data over the past 24 years. Comparing GDP and government debt trends in France, Italy, and Germany provides critical context for the credit rating downgrade and its underlying causes.

The Never-ending Race?: GDP and Debt

When examining cumulative nominal GDP growth, Germany and France have shown similar development over the past 24 years, with 101% growth for Germany and 99% for France. In contrast, Italy has significantly lagged, particularly since 2008, achieving only 76% nominal GDP growth since 2000.

Turning to the government debt-to-GDP ratio, we see that France was similar to Germany until 2009, after which it diverged and began to rise significantly, spiking with the impact of the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Italy, on the other hand, has shown a steady increase in this ratio since 2008.

This raises a critical question: Why has France's debt-to-GDP ratio increased dramatically when GDP growth has been relatively similar to Germany's? The answer is that France's debt has grown much faster than Germany's, as the graph below clearly shows:

The reason for the faster-growing debt has been the high government deficit over the last 24 years:

After the global financial crisis, France ran a government deficit of up to 7% of GDP and needed 10 years to reduce it to 2.25% in 2019. This is remarkable, as government financing costs were suppressed by interest rates that were below 1% from 2009 to 2022 and negative for 8 years during that timeframe:

France’s high deficit is not the sole issue; the core problem lies in its inability to drive higher GDP growth. If the government had effectively used low-interest debt to boost economic development, the debt-to-GDP ratio would be far healthier. France's GDP growth per 1% debt increase is just 0.36%, compared to Italy's 0.65% and Germany's 0.93%, highlighting its inefficiency as an economic investor.

This underperformance has consequences: rising bond yield spreads compared to countries with more stable debt-to-GDP ratios, like Germany.

To identify potential solutions, it is worth examining Italy's strategies during the Eurocrisis for lessons that could guide France forward.

Italy’s Austerity

After the global financial crisis, Italy grappled with significant economic challenges, exacerbated by its already high public debt. Bond yields surged from 4% in 2010 to over 6.5% in 2012, making debt financing increasingly difficult. The turning point came in 2012 when Mario Draghi, then ECB President, delivered his pivotal "Whatever it takes" speech, restoring confidence in the Eurozone and stabilizing markets. Concurrently, the Italian government implemented austerity measures to curb public spending and rebuild trust in its finances. This blend of decisive monetary and fiscal actions restored market confidence, reducing bond yields to around 2% within two years.

Over the past 24 years, Italy’s GDP growth reached just 76%, significantly lagging behind Germany’s 101%, despite both countries taking on similar debt increases (Italy 108%, Germany 117%). This sluggish growth contributed to Italy's rising debt-to-GDP ratio. According to Baccaro and D’Antoni (2020), if Italy had matched Belgium’s growth rate, its public debt in 2007 would have been 90% of GDP instead of 106%.

Italy’s austerity measures from 2012 to 2015 further exacerbated its challenges. These measures caused a 5% drop in GDP, worsening debt rather than reducing it (Storm, 2019; Fazi, 2018). Cutting public spending to balance budgets shrank GDP, reducing revenues and deepening deficits, underscoring the intricate relationship between GDP and debt. Additionally, Italy faced disproportionately high interest payments, allocating 7–15% of annual expenditures to debt servicing, compared to Germany’s 1–7%, which severely limited fiscal flexibility and public investment capacity.

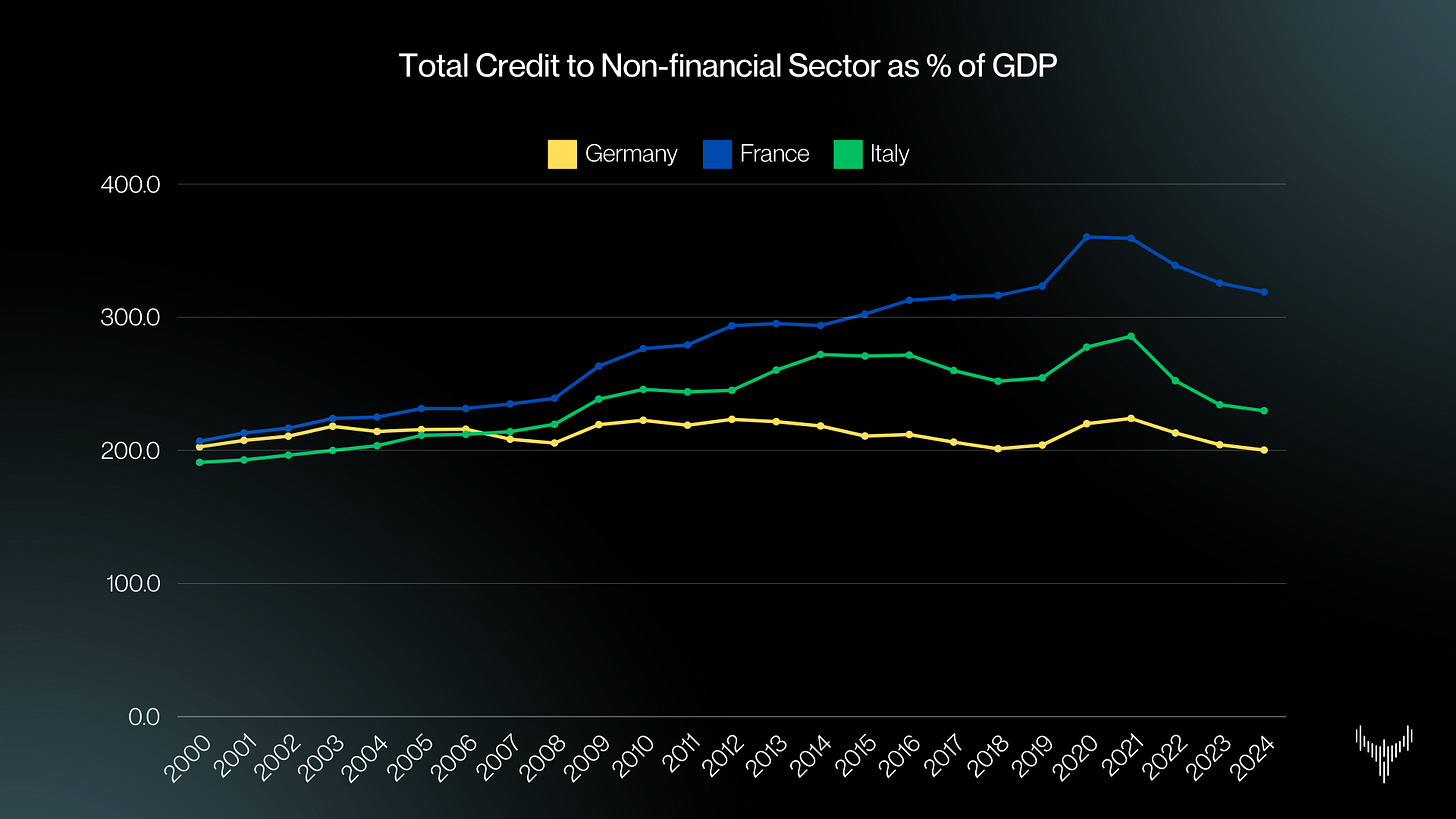

France now faces similar risks, with rising debt and financing costs as the ECB maintains higher interest rates. To avoid Italy’s pitfalls, France must control its debt-to-GDP ratio to reduce interest burdens, improve the efficiency of public spending to drive GDP growth, and stabilize its political landscape to address governance challenges and populist pressures. However, France’s high taxes, including the steepest capital gains rates in Europe (30–34%) and the highest tax-to-GDP ratio in the OECD, restrict its ability to raise revenues further. Combined with rising private and public debt, as noted by the BIS, these factors demand a comprehensive strategy to ensure stability and growth.

Debt Beyond the Government

Data from the BIS Credit of the Non-Financial Sector series shows growth in both public and private-sector debt in France.

With a total credit-to-GDP ratio of 319%, France leads the Eurozone's three largest economies and ranks second among developed countries globally.

Private debt levels play a critical role in assessing a country's vulnerability to economic crises. When considering austerity measures, the dependency of private debt on government spending must be factored in, as reduced government expenditure could exacerbate private-sector vulnerabilities.

Additionally, hidden potential government debt in the form of guaranteed loans warrants attention. Following the Ukraine war, European governments increased loan guarantees for companies affected by rising energy costs. In these arrangements, if a company defaults, the government assumes the debt, increasing public liabilities. Recent Eurostat data shows these guarantees represent significant GDP proportions.

In recent years, Germany and Italy have primarily used this tool to provide liquidity to companies without immediately increasing government debt.

Germany Under pressure

Germany is navigating a challenging economic landscape, primarily driven by the Ukraine war and rising energy costs, which weigh heavily on key industries like chemicals and steel. To provide relief without breaching the constitutional "debt brake" (Schuldenbremse)—capping structural deficits at 0.35% of GDP—the government has relied on guaranteed loans. While this approach offers short-term liquidity without directly increasing public debt, it has not spurred significant investments in an uncertain economic environment, limiting GDP growth.

The shutdown of Germany's last three nuclear power plants in 2023 has heightened reliance on fossil fuels and renewables. Despite ambitious renewable energy targets, the transition has been challenging, with high energy costs and supply concerns prompting companies, particularly in energy-intensive sectors, to delay investments or shift production abroad.

The debt brake itself poses limitations. While it underscores fiscal discipline, it restricts the government’s ability to implement direct economic stimulus or invest in long-term growth. External pressures could also test these fiscal rules. For instance, during Donald Trump’s presidency, calls for increased NATO defense spending and trade protectionism, including tariffs on German exports, strained Germany's economy. A resurgence of such pressures could lead to debates about relaxing the debt brake to enable targeted fiscal measures.

Germany’s political instability further compounds economic challenges. The departure of a coalition party has triggered new elections, scheduled for February, amid rising support for right-leaning nationalist parties like the AfD. Endorsements from high-profile figures such as Elon Musk have bolstered their standing, raising concerns about coalition-building. If the AfD gains significant influence, it could upend Germany’s political landscape, complicating governance as centrist parties refuse to cooperate with them.

These financial, energy, and political challenges are deeply interconnected and mutually reinforcing, leaving Germany vulnerable to economic stagnation and heightened uncertainty. With these dynamics at play, attention turns to the ECB’s role in navigating this complex environment.

The Role of the European Central Bank

The ECB plays a pivotal role in mitigating the compounding debt effect caused by high interest payments, especially as GDP growth lags behind debt expansion. To address this, the ECB can maintain low borrowing costs by either reducing interest rates across the Eurozone or purchasing government bonds in the secondary market to lower yields through increased demand. These tools are critical to stabilizing economies under fiscal strain.

France faces mounting fiscal challenges with its precarious debt-to-GDP ratio, high tax burden, and political instability, leaving limited options for deficit reduction or revenue generation. Reducing government spending could harm GDP growth, as seen in Italy, making France increasingly dependent on ECB support to avoid rising debt servicing costs.

Anticipating ECB Monetary Policy

Post-COVID inflation prompted the ECB to raise interest rates to 4%, later reduced to 3%. However, countries like France and Italy remain vulnerable due to higher debt growth and widening bond spreads. France's interest payments as a share of government expenditure risk reaching Italy’s 10% level, which would severely constrain fiscal flexibility. With current rates above France’s interest payment on debt level of 1.7%, the ECB may need to consider broad rate cuts or targeted interventions to lower French bond yields.

If inflation limits such measures, the ECB could deploy the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) to purchase government bonds from France and Italy, preventing unsustainable debt-to-GDP ratios and elevated interest payments.

The Transmission Protection Instrument

Introduced in 2022 to curb rising Italian bond yields, the TPI has acted as a reliable backstop. Its flexible framework allows the ECB to assist countries like France and Italy while influencing their fiscal policies. By leveraging this tool, the ECB can maintain stability in the Eurozone without immediately reducing overall interest rates.

The Future of the Eurozone

As populist movements gain traction, tensions over fairness and fiscal distribution within the EU are intensifying. The TPI’s targeted bond purchases may provoke perceptions of favoritism, creating divisions among member states. Simultaneously, increasing reliance on state-backed loan guarantees to support economies raises questions about long-term debt sustainability and coordination across the bloc.

The aftermath of Brexit underscored the economic risks of leaving the EU, yet dissatisfaction in some member states could reignite debates about exits. The ability of the EU and ECB to address these challenges will determine whether they can sustain the Eurozone’s unity and ensure its economic resilience.

Bitcoin: An antidote for debt?

In conclusion, Bitcoin emerges not only as a hedge for individuals but as a strategic lifeline for European institutions grappling with the Eurozone’s deepening economic and political crises. Its decentralized, debt-free structure and fixed supply make it immune to the inflationary pressures and fiscal mismanagement that plague fiat currencies. Bitcoin’s geopolitical neutrality and global accessibility position it as an unparalleled asset, free from the influence of major powers like the U.S. or China. For European institutions seeking to diversify away from euro risk and reduce dependency on dollar-dominated financial systems, Bitcoin offers a compelling alternative. Its unseizable nature and resistance to wealth confiscation measures, taxation, or capital controls further reinforce its value, especially in times of political upheaval. As wealth preservation becomes increasingly challenging in the face of rising debt-to-GDP ratios and fragmented governance, Bitcoin provides a sovereign, incorruptible means to store and transport wealth. In a rapidly evolving financial landscape, Bitcoin is not just a beneficiary of the Eurozone’s challenges—it is the antidote to them.

Disclaimers:

This is not an offering. This is not financial advice. Always do your own research.

Our discussion may include predictions, estimates or other information that might be considered forward-looking. While these forward-looking statements represent our current judgment on what the future holds, they are subject to risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially. You are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements, which reflect our opinions only as of the date of this presentation. Please keep in mind that we are not obligating ourselves to revise or publicly release the results of any revision to these forward-looking statements in light of new information or future events.

Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.